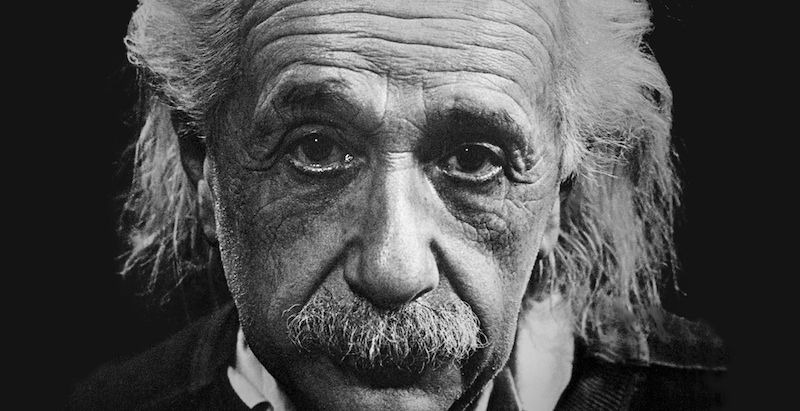

‘Something Like My Own Obituary.’ Albert Einstein on Skepticism, Reason, and Truth

Here I sit in order to write, at the age of 67, something like my own obituary. I am doing this not merely because Dr. Schilpp has persuaded me to do it, but because I do, in fact, believe that it is a good thing to show those who are striving alongside of us how our own striving and searching appears in retrospect. After some reflection, I felt how imperfect any such attempt is bound to be. For, however brief and limited one’s working life may be, and however predominant may be the way of error, the exposition of that which is worthy of communication does nonetheless not come easy—today’s person of 67 is by no means the same as was the one of 50, of 30, or of 20.

Every reminiscence is colored by one’s present state, hence by a deceptive point of view. This consideration could easily deter one. Nevertheless much can be gathered out of one’s own experience that is not open to another consciousness.

When I was a fairly precocious young man I became thoroughly impressed with the futility of the hopes and strivings that chase most men restlessly through life. Moreover, I soon discovered the cruelty of that chase, which in those years was much more carefully covered up by hypocrisy and glittering words than is the case today. By the mere existence of his stomach everyone was condemned to participate in that chase. The stomach might well be satisfied by such participation, but not man insofar as he is a thinking and feeling being.

As the first way out there was religion, which is implanted into every child by way of the traditional education-machine. Thus I came—though the child of entirely irreligious (Jewish) parents—to a deep religiousness, which, however, reached an abrupt end at the age of 12. Through the reading of popular scientific books I soon reached the conviction that much in the stories of the Bible could not be true. The consequence was a positively fanatic [orgy of] freethinking coupled with the impression that youth is intentionally being deceived by the state through lies; it was a crushing impression.

What, precisely, is “thinking”? When, on the reception of sense impressions, memory pictures emerge, this is not yet “thinking.”Mistrust of every kind of authority grew out of this experience, a skeptical attitude toward the convictions that were alive in any specific social environment—an attitude that has never again left me, even though, later on, it has been tempered by a better insight into the causal connections.

It is quite clear to me that the religious paradise of youth, which was thus lost, was a first attempt to free myself from the chains of the “merely personal,” from an existence dominated by wishes, hopes, and primitive feelings. Out yonder there was this huge world, which exists independently of us human beings and which stands before us like a great, eternal riddle, at least partially accessible to our inspection and thinking. The contemplation of this world beckoned as a liberation, and I soon noticed that many a man whom I had learned to esteem and to admire had found inner freedom and security in its pursuit.

The mental grasp of this extra-personal world within the frame of our capabilities presented itself to my mind, half consciously, half unconsciously, as a supreme goal. Similarly motivated men of the present and of the past, as well as the insights they had achieved, were the friends who could not be lost. The road to this paradise was not as comfortable and alluring as the road to the religious paradise; but it has shown itself reliable, and I have never regretted having chosen it.

What I have said here is true only in a certain sense, just as a drawing consisting of a few strokes can do justice to a complicated object, full of perplexing details, only in a very limited sense. If an individual enjoys well-ordered thoughts, it is quite possible that this side of his nature may grow more pronounced at the cost of other sides and thus may determine his mentality in increasing degree. In this case it may well be that such an individual sees in retrospect a uniformly systematic development, whereas the actual experience takes place in kaleidoscopic particular situations.

The great variety of the external situations and the narrowness of the momentary content of consciousness bring about a sort of atomizing of the life of every human being. In a man of my type, the turning point of the development lies in the fact that gradually the major interest disengages itself to a far-reaching degree from the momentary and the merely personal and turns toward the striving for a conceptual grasp of things. Looked at from this point of view, the above schematic remarks contain as much truth as can be stated with such brevity.

What, precisely, is “thinking”? When, on the reception of sense impressions, memory pictures emerge, this is not yet “thinking.” And when such pictures form sequences, each member of which calls forth another, this too is not yet “thinking.” When, however, a certain picture turns up in many such sequences, then—precisely by such return—it becomes an organizing element for such sequences, in that it connects sequences in themselves unrelated to each other.

Such an element becomes a tool, a concept. I think that the transition from free association or “dreaming” to thinking is characterized by the more or less preeminent role played by the “concept.” It is by no means necessary that a concept be tied to a sensorily cognizable and reproducible sign (word); but when this is the case, then thinking becomes thereby capable of being communicated.

With what right—the reader will ask—does this man operate so carelessly and primitively with ideas in such a problematic realm without making even the least effort to prove anything? My defense: all our thinking is of this nature of free play with concepts; the justification for this play lies in the degree of comprehension of our sensations that we are able to achieve with its aid. The concept of “truth” cannot yet be applied to such a structure; to my thinking this concept becomes applicable only when a far-reaching agreement (convention) concerning the elements and rules of the game is already at hand.

At the age of 12 I experienced a second wonder . . . in a little book dealing with Euclidean plane geometry, which came into my hands at the beginning of a school year.I have no doubt but that our thinking goes on for the most part without use of signs (words) and beyond that to a considerable degree unconsciously. For how, otherwise, should it happen that sometimes we “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” appears to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts already sufficiently fixed within us. Whenever such a conflict is experienced sharply and intensively it reacts back upon our world of thought in a decisive way. The development of this world of thought is in a certain sense a continuous flight from “wonder.”

A wonder of this kind I experienced as a child of four or five years when my father showed me a compass. That this needle behaved in such a determined way did not at all fit into the kind of occurrences that could find a place in the unconscious world of concepts (efficacy produced by direct “touch”). I can still remember—or at least believe I can remember—that this experience made a deep and lasting impression upon me.

Something deeply hidden had to be behind things. What man sees before him from infancy causes no reaction of this kind; he is not surprised by the falling of bodies, by wind and rain, nor by the moon, nor by the fact that the moon does not fall down, nor by the differences between living and nonliving matter.

At the age of 12 I experienced a second wonder of a totally different nature—in a little book dealing with Euclidean plane geometry, which came into my hands at the beginning of a school year. Here were assertions, as for example the intersection of the three altitudes of a triangle at one point, that—though by no means evident—could nevertheless be proved with such certainty that any doubt appeared to be out of the question. This lucidity and certainty made an indescribable impression upon me. That the axioms had to be accepted unproved did not disturb me.

In any case it was quite sufficient for me if I could base proofs on propositions whose validity appeared to me beyond doubt. For example, I remember that an uncle told me about the Pythagorean theorem before the holy geometry booklet had come into my hands. After much effort I succeeded in “proving” this theorem on the basis of the similarity of triangles; in doing so it seemed to me “evident” that the relations of the sides of the right-angled triangles would have to be completely determined by one of the acute angles.

Only whatever did not in similar fashion seem to be “evident” appeared to me to be in need of any proof at all. Also, the objects with which geometry is concerned seemed to be of no different type from the objects of sensory perception, “which can be seen and touched.” This primitive conception, which probably also lies at the bottom of the well-known Kantian inquiry concerning the possibility of “synthetic judgments a priori,” rests obviously upon the fact that the relation of geometrical concepts to objects of direct experience (rigid rod, finite interval, etc.) was unconsciously present.

If thus it appeared that it was possible to achieve certain knowledge of the objects of experience by means of pure thinking, this “wonder” rested upon an error. Nevertheless, for anyone who experiences it for the first time, it is marvelous enough that man is capable at all of reaching such a degree of certainty and purity in pure thinking as the Greeks showed us for the first time to be possible in geometry.

__________________________________

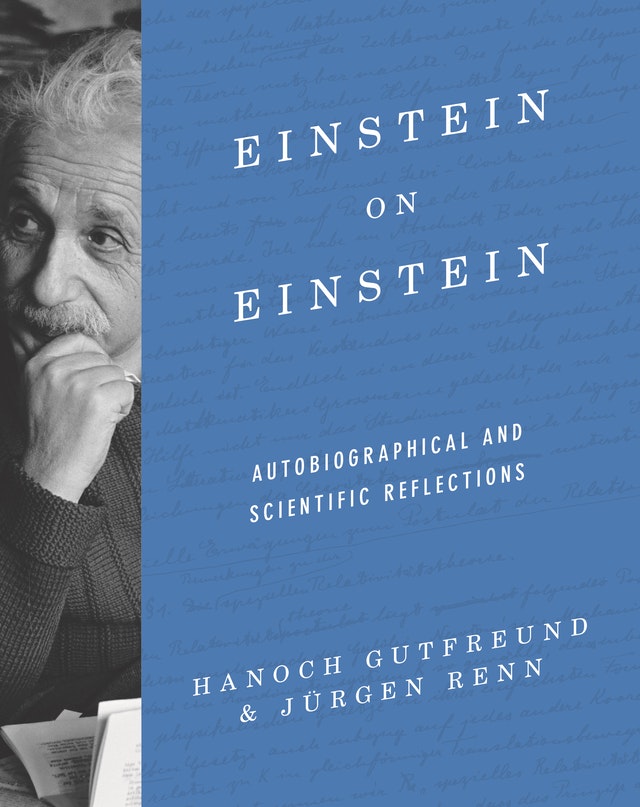

Excerpted from Hanoch Gutfreund & Jürgen Renn’s Einstein on Einstein © 2020 Princeton University Press. From Albert Einstein’s ‘Autobiographical Notes’ Translated from the original German manuscript by Paul Arthur Schilpp and revised with the help of Professor Peter Bergmann of Syracuse University.