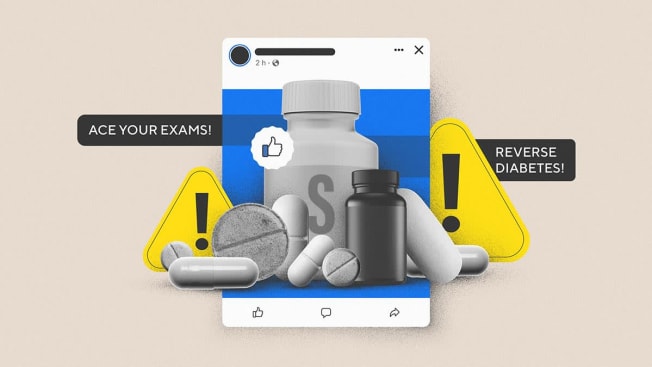

Marketers Are Using Facebook to Promote Dangerous or Illegal Supplements

Consumer Reports found ads for products claiming to treat diabetes or boost brainpower targeted to vulnerable users

By Kaveh Waddell

Dangerous or illegal dietary supplements are regularly promoted or advertised on Facebook, Consumer Reports has found. And in some cases, Facebook hosts product listings for these supplements on its marketplace.

In one example, a post in May by a supplements store in Alabama advertises a sleep aid that contains phenibut, a potentially dangerous substance that the Food and Drug Administration forbids manufacturers from adding to dietary supplements.

In another, a series of posts from a Facebook page bearing a blue “verified” check mark trumpets the virtues of consuming comfrey, a flowering plant that’s illegal to sell for oral consumption in the U.S. because it can contain liver-damaging substances.

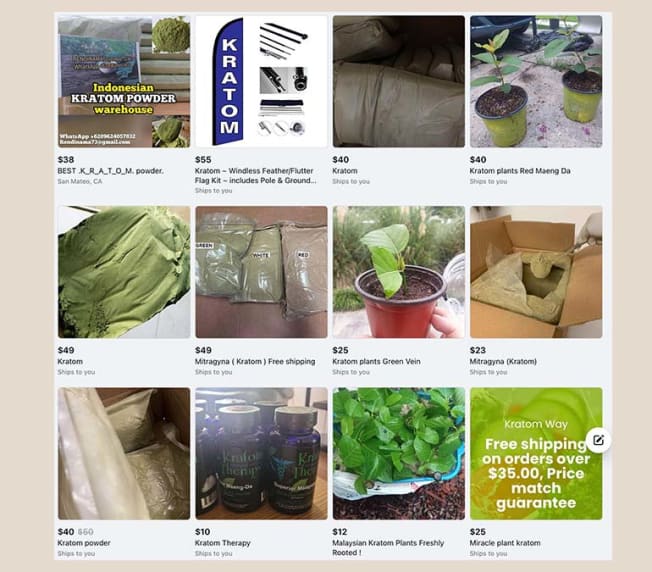

And a search for “kratom” on Facebook Marketplace brings up a number of product listings, some with offers of free shipping. The Drug Enforcement Agency lists kratom as a “drug of concern,” and Federal Drug Administration testing in 2019 found elevated levels of lead and nickel in kratom products, which it warned could leave long-term users with heavy metal poisoning.

CR found these examples by searching Facebook and Facebook’s public ad library. We also used a reporting tool called Citizen Browser, which was developed by The Markup, a nonprofit newsroom. Facebook’s ad library shows all the ads that could potentially be seen by any users, while Citizen Browser offers an inside look at what real users see in their feeds.

Some of the content CR found on Facebook appears to violate the policies of its parent company, Meta. The platform doesn’t allow users to post content promoting “non-medical drugs” or buy or sell pharmaceutical drugs.

It also forbids advertisements that promote the sale or use of “unsafe substances,” including dangerous supplements. What counts as an unsafe supplement, though, isn’t clear. The policy says violations are determined by the company “in its sole discretion,” but it singles out comfrey in a handful of examples of unsafe substances.

A Facebook spokesperson said the kratom listings violated the platform’s rules, but that the posts about comfrey and phenibut—which were not paid Facebook advertisements—did not.

On Wednesday, most listings for kratom had disappeared from Facebook Marketplace, but at least one still appeared at the top of a search.

Ads Target Vulnerable Users

Some ads for supplements use Facebook’s marketing tools to target specific groups of people, according to data from Citizen Browser.

One example, from a supplements company called New Life USA, teases what sounds like a miracle cure for diabetes. The ad reads, “This diabetes type 2 patient just ate a Walmart pie without headaches or a spike in his sugar levels. 🤯” (An alternate version, aimed perhaps at a slightly different audience, replaces the Walmart pie for a Costco sandwich.)

Both versions, which Citizen Browser panelists saw early this year, used Facebook’s ad-targeting tools to appear in front of people that Facebook thinks are interested in diabetes awareness. Users who clicked on the attached links would end up on New Life’s website, where until recently they could buy a $229 “Reverse Diabetes Package.”

Images From New Life USA Ads

These ads, which linked to a "Diabetes Reversal Presentation," were targeted to Facebook users interested in diabetes awareness.

Source: Citizen Browser

New Life USA took down that product listing last week as CR was reporting this article, but the individual supplements in the package still appear to be available on the company’s website.

New Life’s CEO, Richard Harrison, MD, told CR he thinks that people with diabetes should continue to work with their doctors, but he also says they should “wean [themselves] off medication.”

Medical experts warn that supplements marketed at people with diabetes are generally ineffective at best and harmful at worst.

According to the National Institutes of Health, a few supplements have “weak evidence of a possible benefit,” but for a majority of supplements, “there isn’t evidence to support a beneficial effect on diabetes or its complications.” The FDA has sent warning letters in the past to companies that market supplements with claims that they “cure, treat, mitigate, or prevent diabetes.”

Asked about the New Life USA ads, Pieter Cohen, MD, a Harvard Medical School assistant professor who studies supplements, said, “This example is really insidious.”

“Facebook getting those advertisements in front of people with diabetes is extremely problematic, because no supplements have been proven to help diabetes,” Cohen says. “If people turn to these unproven supplements, they may not seek care from their doctors or may choose not to take the medications that are proven to have long-term positive effects.”

In another example of hyper-targeted supplement advertising, a company called Healthycell touts an “ultimate brain supplement” with ads that say, “Students trust us to ace their exams.” The ads link to a $59.95 “science-backed” product called Focus + Recall.

Citizen Browser said that the Healthycell ads, which our panelists saw in March, targeted Facebook users as young as 18 years old, plus those who are interested in “women in STEM fields,” one of Facebook’s interest categories. (STEM stands for science, technology, engineering, and math.)

Other nootropic supplements—products that promise to boost brainpower—target people who are interested in neuroscience, memory, or fitness.

“It’s problematic to be pushing nootropics onto students or young people entering the workforce,” Cohen says. “There’s no proof that anything sold as a nootropic will actually help you do better work or help you think clearer.” (There’s an exception, Cohen says: Natural caffeine in low doses can improve cognition for some people.)

Facebook said the New Life USA and Healthycell ads violated its advertising policies, which don’t allow marketers to promote or sell unsafe substances. The New Life ads stopped running earlier this year. Facebook took down the Healthycell ad after CR asked about it.

In an email, Healthycell’s CEO, Douglas Giampapa, pointed CR to three small studies that hinted at potential cognitive benefits for some ingredients in the Focus + Recall nootropic supplement. In one example, a 2008 study of 27 people by Unilever researchers suggested that caffeine and L-theanine, two ingredients in the Focus + Recall product, are “beneficial for improving performance on cognitively demanding tasks” when combined.

Asked about the ads CR found on Facebook, Giampapa said, “While we make our Focus + Recall supplement primarily for older adults, we found that students were buying it as a healthy alternative to sugar-saturated energy drinks with massive amounts of caffeine.”

Facebook should police ads far more strictly to keep potentially harmful information or products off its platform, says Nathalie Maréchal, PhD, policy director at Ranking Digital Rights, a nonprofit that grades tech companies on their content moderation practices and other factors.

Maréchal also thinks the company should be more forthcoming about how it moderates ads. In its “Big Tech Scorecard,” a report that ranks social media companies on their policies toward privacy and freedom of expression, her group criticized Facebook’s parent company, Meta, for leaving advertising out of its annual transparency reports.

Supplements With Dangerous Unknowns

The fact that these products are easily found on Facebook—and in some cases advertised to people who aren’t actively looking for supplements—is especially alarming given the many known problems with how supplements are marketed and sold in the U.S.

Cohen and other researchers have found illegal, unapproved, or potentially harmful substances in hundreds of dietary supplements, including some nootropics. In an August study published in the journal Clinical Toxicology, Cohen and two co-authors found that seven over-the-counter supplements sold for cognitive enhancement contained centrophenoxine, a drug that the FDA hasn’t approved for sale in the U.S.

And last month, an investigation published in the journal JAMA Network Open analyzed 30 supplements marketed with claims that they boost the immune system, all purchased from Amazon. Of the 30, 17 had inaccurate labels, and nine of those mislabeled products had components that didn’t appear on the label at all.

Listings for "Kratom" on Facebook Marketplace

Facebook took down many of these listings when CR inquired about them, but at least one reappeared soon afterward. The DEA lists kratom as a "drug of concern."

Source: Facebook Marketplace

CR’s own testing in 2019 found that many popular echinacea and turmeric supplements contained elevated lead or bacteria levels.

When you take a supplement, you can’t always know for sure what it contains. Sometimes those unknowns are dangerous. About 23,000 emergency room visits per year result from adverse reactions to supplements, according to a 2015 study in The New England Journal of Medicine, leading to about 2,150 hospitalizations a year.

Legally, supplement makers can make certain broad claims about their products as long as they don’t specifically say they’re curing or preventing diseases. Only drugmakers are allowed to say that, when they can prove it. This is why you’ll often see supplements claiming to “support brain function,” or “promote balanced glucose levels.”

Most of the claims CR found on Facebook fall into this permitted category. One popular nootropic supplement, for example, is marketed as helping to promote “cognitive power and performance.” But others, like the ads from New Life USA, may cross the line by claiming products can “reverse diabetes.”

In a decade-old study of 127 supplements intended for weight loss and immune system support, the FDA’s parent agency found that even when manufacturers published the types of claims they’re allowed to make, those vague claims were still rarely backed by sufficient, reliable evidence.

Lax Regulations for Supplements

Oversight of supplements is split between the FDA and the Federal Trade Commission. The FDA handles safety and labeling, while the FTC polices advertising.

But the FDA doesn’t regulate supplements the way it regulates drugs. Supplements are treated more like food, which is why manufacturers don’t have to meet the rigorous standards that drug companies do.

A nationally representative CR survey of 3,070 US adults from the summer of 2022 found that about three-quarters of Americans take supplements at least once a week. The survey also found that about a third mistakenly thought it’s true or mostly true that the FDA tests supplements for safety, and one-quarter said they didn’t know if that was the case.

In fact, bipartisan legislation proposed in Congress last spring would give the FDA some additional oversight. The bill would require manufacturers to tell the FDA about every supplement they produce and exactly what’s in those products. The FDA would then make that information available to the public. In a 2019 survey, Pew found 95 percent of people who used supplements said they would support rules that would require manufacturers to report this information to the FDA.

“The FDA currently has no systematic way of knowing what dietary supplements are on the market, when new products are introduced, or what they contain—even if they contain ingredients we have previously acted against,” says an FDA spokesperson, Courtney Rhodes. If supplements were required to be listed with the agency, Rhodes says, it would be able to take action against new products that have illegal ingredients.

But the bill doesn’t give the FDA any new powers to regulate supplements. Some consumer advocates and medical experts, including Harvard’s Cohen, are calling for rules that would give the FDA tools to verify supplement makers’ submissions to the proposed supplements database, or cut down on the types of claims companies can make without providing evidence.

“Congress should directly strengthen FDA’s authority to block and remove dangerous and illegal supplements before they are put on sale online or made available in retail stores,” says Chuck Bell, programs director for advocacy at CR. “With over 85,000 supplements in the marketplace and thousands more being added each year, the FDA really needs to up its game on supplement safety. Otherwise, we will continue to have a marketplace that is riddled with products that contain illegal ingredients and prescription drugs.”

The FTC declined to comment on CR’s findings.

For now, supplements remain relatively unregulated, which means it still falls on you to be careful about consuming supplements.

If you’re shopping for supplements in a walk-in store, you probably won’t get much help from pharmacists or other employees. When CR sent secret shoppers to 34 stores—including Costco, Walmart, Target, Walgreens, CVS, GNC, and The Vitamin Shoppe—store workers usually weren’t familiar with potential risks from taking supplements and didn’t warn them about dangers like interactions with medications.

You can look instead for seals from organizations that test supplements, such as UL Solutions, ConsumerLab.com, NSF International, and U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP). These seals verify that a supplement actually contains the ingredients listed on the label. But that doesn’t mean the ingredients won’t put you at risk for serious side effects.

You should definitely avoid a supplement that has any of these 15 dangerous ingredients.

In general, CR recommends checking with your doctor before trying new supplements, and searching for information about them in official sources like the NIH’s MedlinePlus.gov.

Consumer Reports is an independent, nonprofit organization that works side by side with consumers to create a fairer, safer, and healthier world. CR does not endorse products or services, and does not accept advertising. Copyright © 2022, Consumer Reports, Inc.