Go Ahead, Bribe Me to Do the Right Thing

One evening some years ago, my brother was suffering through a frustrating round of put down the video game controller and do your math homework with his 12-year-old son. “What do I have to do?” he blurted out angrily. “Pay you?”

His son paused the game, looked up at him, and said, “How much?”

Caught off guard, my brother suggested 25 cents a problem. His son ran straight upstairs and came down 20 minutes later with his homework and a verbal invoice for $2. But when he asked for the same deal the next night, my brother refused. “No son of mine is going to have to get paid to do homework,” he later told me. As it turned out, no son of his would ever willingly do his math homework again.

[Read: Don’t help your kids with homework]

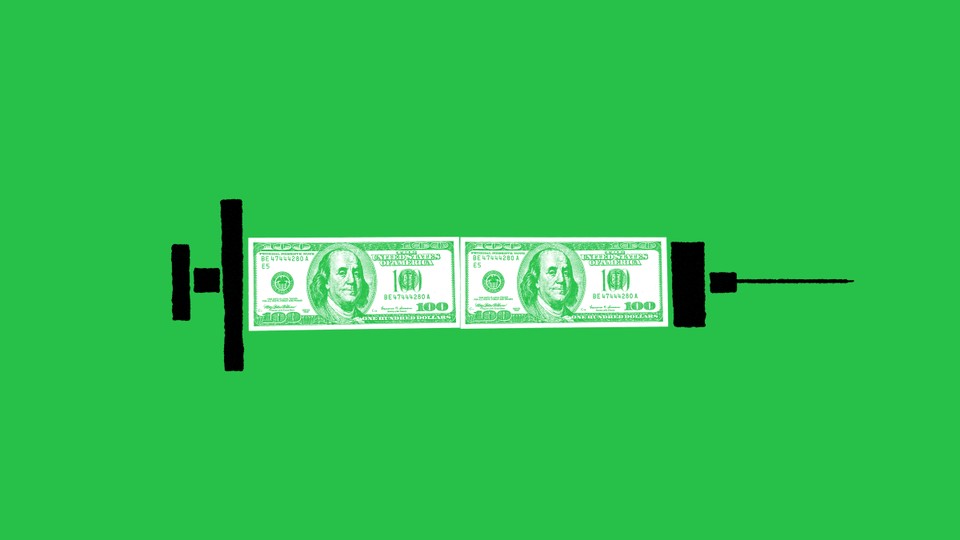

I thought of this recently when a stream of grumbling turned up in my Twitter feed over incentives that are being offered to encourage Americans to get a COVID-19 vaccine. These include money, beer, donuts, and (in a brief campaign called “Joints for Jabs”) weed. Tweeted one commentator: “A sense of decency and community isn’t enough to make people do what is right to preserve the lives of others. They have to be cajoled and bribed to do it. Sometimes don’t you just hate humans?”

The idea that society is better off when people act on “intrinsic” motivation—that is, because they’re inclined to do the right thing—and not on“extrinsic” motivation, such as receiving a cash payment, is widespread. But is there something inherently wrong with bribing people to do the right thing? And on a practical level, does it work?

They’re not entirely independent questions, because humans are biased. Someone who feels that incentives are unseemly is probably especially open to the idea that they’re ineffective. Researchers are no exception; beginning in the early 1970s, a number of psychologists devoted themselves to pushing back against the theory that human behavior can easily be bent with a yummy treat. The result was the discovery of the “overjustification effect,” the notion that incentives don’t merely fail, but actually sap intrinsic motivation—meaning that people, especially children, who might otherwise be willing to do things become less willing to do them when incentives are placed on the table.

Many of the scientific papers these psychologists produced bore damning titles (such as “Undermining Children’s Interest With Extrinsic Rewards”), but the fine print was a mood killer. Matthew Normand, a psychologist at the University of the Pacific who studies how to change people’s behavior, told me, “There are major problems with that literature.” The overjustification effect was seen only in repetitive tasks, and only in the first few repetitions, after which the effect went away. Plus, it seemed to act only on people who were happy to do the job in the first place. Most studies concluded that there was little or nothing to the effect.

Nonetheless, the idea that incentives backfire was seductive, and proved hard to shake. In 2009, it got a boatload of PR with the appearance of Daniel Pink’s best-selling book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. In the opening pages, Pink, a sort of how-to-succeed-in-business-through-pop-psychology writer, tells the story of an obscure 1940s experiment on monkey bribery. The study found that eight rhesus monkeys happily solved puzzles for fun but did a worse job when they were given raisins as a reward. The only thing that study probably proved was that monkeys sometimes get bored with raisins. The experimenters quietly abandoned the study for more promising research, and the rest of the field ignored it. But when Pink wrote that the findings “should have changed the world,” many readers took him at his word.

In the real world and in most studies, incentives tend to work just fine. They have been used to help drug users get and stay clean and to encourage people with HIV to take their medications. When the UCLA COVID-19 Health and Politics Project surveyed unvaccinated Americans, it found that roughly a third said they would be more likely to get the shot if they received $100. Incentives are so widely deployed and validated that citing specific research defending them feels almost silly—it’s like having to offer proof that the internal combustion engine makes cars go.

Despite all the evidence in favor of public-health incentives, America has been slow to adopt them, at least until now. (San Francisco and the Department of Veterans Affairs are two notable exceptions.) What’s held us back? Maybe it’s our lack of a strong public-health system, or the sense that the government shouldn’t interfere too much with people’s choices. Or maybe it’s our Puritan ethic that favors morality over transaction.

[Read: No one actually knows if you’re vaccinated]

But these explanations tend to align with conservative values, and much of the griping about vaccine incentives seems to be coming from the left. Some scolds have expressed concerns that bribing people with such tools of the devil as donuts, lottery tickets, beer, and hot dogs will make people like these unhealthy indulgences. But that’s confused thinking. Things serve as rewards only for people who already like them. If your boss rewarded you for your good work by dumping her trash can on your desk, would you suddenly be thrilled by trash heaps?

Maybe the progressives I follow on Twitter are still enamored of the Drive myth, with its vaguely anti-capitalist portrayal of people prepared to do the right thing if their innate cooperative impulses aren’t corrupted by rewards. Maybe they’re displaying animosity toward the right and its general noncompliance with COVID-19 measures, given that the vaccine-hesitant are mostly Republicans. Perhaps, least charitably, the early-vaccinated feel a touch of resentment for having missed out on the goodies. (I confess, a free beer would have been nice when I got my vaccine.)

Whatever the origins of the objections, Normand frets that they might feed into a dangerous incentive hesitancy. “Sure, people should do it without needing an incentive,” he said. “But what’s the alternative to not offering them? Not enough people get vaccinated, and we’re stuck with a public-health crisis.”

Some incentives may work better than others. Ayelet Gneezy, a behavioral scientist and the director of the Center for Social Innovation and Impact at the UC San Diego School of Management, is bullish on vaccine incentives, but she thinks non-monetary rewards will work best. Modest payments could backfire by hardening the position of those who have been refusing the vaccine out of principle, she told me, because taking the incentive will feel like selling out. Beer, donuts, and hot dogs sound like winners to her.

But the selling-your-soul-for-money effect could be helpful, notes Michael Hallsworth, the managing director of the North American subsidiary of a think tank called the Behavioural Insights Team. He pointed me to a 2014 study that found that people who refused to do something in order to maintain solidarity with their friends’ beliefs actually liked being able to use a bribe as an excuse. “I did it for the money” is apparently easier to sell to your pals than “I disagree.” Hallsworth’s example of a clever incentive: Ohio offered to enter the newly vaccinated in a series of $1 million lotteries.

[Conor Friedersdorf: Put Anthony Fauci in a dunk tank]

If the whole intrinsic-versus-extrinsic-motivation debate seems a little convoluted, that may be because it’s based on a false premise: that they’re not the same thing. “I don’t think there’s any evidence that there’s a qualitative difference between them,” Normand said. “All of our behavior is a product of incentives. Most of the incentives are mediated by the social environment, so they’re not as noticeable, but it’s a mistake to put them in a different category from what we call external incentives.”

Less noticeable incentives to refuse the vaccine could include the approval of friends or of popular anti-vaccination figures, or maybe just the cow-tipping good fun of owning the libs. In that light, tangible incentives to get vaccinated seem less like bribery and more like leveling the playing field.

I asked my brother how he felt about vaccine incentives, and he surprised me by saying he was all for them. In fact, he added, looking back, he wishes he had kept paying his son to do the math, at least long enough to get him into the habit. What changed his mind? “Back then, I thought I’d find a better solution,” he told me. “But I never did.”

If we can’t vaccinate enough people to bring the pandemic to an end, I imagine many of today’s anti-incentivers will have the same regrets.