Can Buddhism Fix AI?

Photographs by Venice Gordon

The monk paces the Zendo, forecasting the end of the world.

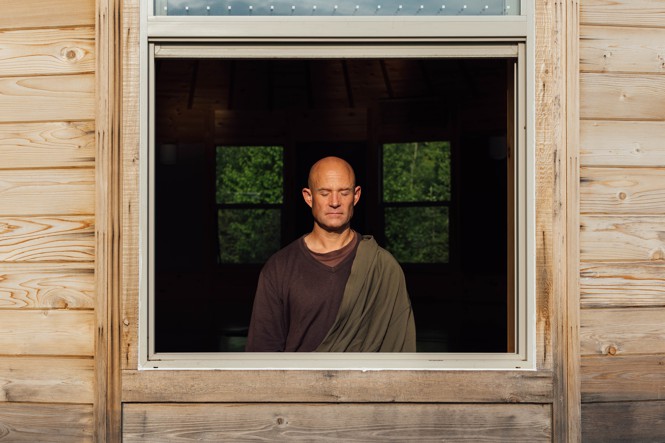

Soryu Forall, ordained in the Zen Buddhist tradition, is speaking to the two dozen residents of the monastery he founded a decade ago in Vermont’s far north. Bald, slight, and incandescent with intensity, he provides a sweep of human history. Seventy thousand years ago, a cognitive revolution allowed Homo sapiens to communicate in story—to construct narratives, to make art, to conceive of god. Twenty-five hundred years ago, the Buddha lived, and some humans began to touch enlightenment, he says—to move beyond narrative, to break free from ignorance. Three hundred years ago, the scientific and industrial revolutions ushered in the beginning of the “utter decimation of life on this planet.”

Humanity has “exponentially destroyed life on the same curve as we have exponentially increased intelligence,” he tells his congregants. Now the “crazy suicide wizards” of Silicon Valley have ushered in another revolution. They have created artificial intelligence.

Human intelligence is sliding toward obsolescence. Artificial superintelligence is growing dominant, eating numbers and data, processing the world with algorithms. There is “no reason” to think AI will preserve humanity, “as if we’re really special,” Forall tells the residents, clad in dark, loose clothing, seated on zafu cushions on the wood floor. “There’s no reason to think we wouldn’t be treated like cattle in factory farms.” Humans are already destroying life on this planet. AI might soon destroy us.

[From the July/August 2023 issue: The coming humanist renaissance]

For a monk seeking to move us beyond narrative, Forall tells a terrifying story. His monastery is called MAPLE, which stands for the “Monastic Academy for the Preservation of Life on Earth.” The residents there meditate on their breath and on metta, or loving-kindness, an emanation of joy to all creatures. They meditate in order to achieve inner clarity. And they meditate on AI and existential risk in general—life’s violent, early, and unnecessary end.

Does it matter what a monk in a remote Vermont monastery thinks about AI? A number of important researchers think it does. Forall provides spiritual advice to AI thinkers, and hosts talks and “awakening” retreats for researchers and developers, including employees of OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Apple. Roughly 50 tech types have done retreats at MAPLE in the past few years. Forall recently visited Tom Gruber, one of the inventors of Siri, at his home in Maui for a week of dharma dinners and snorkeling among the octopuses and neon fish.

Forall’s first goal is to expand the pool of humans following what Buddhists call the Noble Eightfold Path. His second is to influence technology by influencing technologists. His third is to change AI itself, seeing whether he and his fellow monks might be able to embed the enlightenment of the Buddha into the code.

Forall knows this sounds ridiculous. Some people have laughed in his face when they hear about it, he says. But others are listening closely. “His training is different from mine,” Gruber told me. “But we have that intellectual connection, where we see the same deep system problems.”

Forall describes the project of creating an enlightened AI as perhaps “the most important act of all time.” Humans need to “build an AI that walks a spiritual path,” one that will persuade the other AI systems not to harm us. Life on Earth “depends on that,” he told me, arguing that we should devote half of global economic output—$50 trillion, give or take—to “that one thing.” We need to build an “AI guru,” he said. An “AI god.”

His vision is dire and grand, but perhaps that is why it has found such a receptive audience among the folks building AI, many of whom conceive of their work in similarly epochal terms. No one can know for sure what this technology will become; when we imagine the future, we have no choice but to rely on myths and forecasts and science fiction—on stories. Does Forall’s story have the weight of prophecy, or is it just one that AI alarmists are telling themselves?

In the Zendo, Forall finishes his talk and answers a few questions. Then it is time for “the most fun thing in the world,” he says, his self-seriousness evaporating for a second. “It’s pretty close to the maximum amount of fun.” The monks stand tall before a statue of the Buddha. They bow. They straighten up again. They get down on their hands and knees and kiss their forehead to the earth. They prostrate themselves in unison 108 times, as Forall keeps count on a set of mala beads and darkness begins to fall over the Zendo.

The world is witnessing the emergence of an eldritch new force, some say, one humans created and are struggling to understand.

AI systems simulate human intelligence.

AI systems take an input and spit out an output.

AI systems generate those outputs via an algorithm, one trained on troves of data scraped from the web.

AI systems create videos, poems, songs, pictures, lists, scripts, stories, essays. They play games and pass tests. They translate text. They solve impossible problems. They do math. They drive. They chat. They act as search engines. They are self-improving.

AI systems are causing concrete problems. They are providing inaccurate information to consumers and are generating political disinformation. They are being used to gin up spam and trick people into revealing sensitive personal data. They are already beginning to take people’s jobs.

[Annie Lowrey: AI isn’t omnipotent. It’s janky.]

Beyond that—what they can and cannot do, what they are and are not, the threat they do or do not pose—it gets hard to say. AI is revolutionary, dangerous, sentient, capable of reasoning, janky, likely to kill millions of humans, likely to enslave millions of humans, not a threat in and of itself. It is a person, a “digital mind,” nothing more than a fancy spreadsheet, a new god, not a thing at all. It is intelligent or not, or maybe just designed to seem intelligent. It is us. It is something else. The people making it are stoked. The people making it are terrified and suffused with regret. (The people making it are getting rich, that’s for sure.)

In this roiling debate, Forall and many MAPLE residents are what are often called, derisively if not inaccurately, “doomers.” The seminal text in this ideological lineage is Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence, which posits that AI could turn humans into gorillas, in a way. Our existence could depend not on our own choices but on the choices of a more intelligent other.

Amba Kak, the executive director of the AI Now Institute, summarized this view: “ChatGPT is the beginning. The end is, we’re all going to die,” she told me earlier this year, while rolling her eyes so hard I swear I could hear it through the phone. She described the narrative as both self-flattering and cynical. Tech companies have an incentive to make such systems seem otherworldly and impossible to regulate, when they are in fact “banal.”

Forall is not, by any means, a coder who understands AI at the zeros-and-ones level; he does not have a detailed familiarity with large language models or algorithmic design. I asked him whether he had used some of the popular new AI gadgets, such as ChatGPT and Midjourney. He had tried one chatbot. “I just asked it one question: Why practice?” (He meant “Why should a person practice meditation?”)

Did he find the answer satisfactory?

“Oh, not really. I don’t know. I haven’t found it impressive.”

His lack of detailed familiarity with AI hasn’t changed his conclusions on the technology. When I asked whom he looks to or reads in order to understand AI, he at first, deadpan, answered, “the Buddha.” He then clarified that he also likes the work of the best-selling historian Yuval Noah Harari and a number of prominent ethical-tech folks, among them Zak Stein and Tristan Harris. And he is spending his life ruminating on AI’s risks, which he sees as far from banal. “We are watching humanist values, and therefore the political systems based on them, such as democracy, as well as the economic systems—they’re just falling apart,” he said. “The ultimate authority is moving from the human to the algorithm.”

Forall has been worried about the apocalypse since he was 4. In one of his first memories, he is standing in the kitchen with his mother, just a little shorter than the trash can, panicking over people killing one another. “I remember telling her with the expectation that somehow it would make a difference: ‘We have to stop them. Just stop the people from killing everybody,’” he told me. “She said ‘Yes’ and then went back to chopping the vegetables.” (Forall’s mother worked for humanitarian nonprofits and his father for conservation nonprofits; the household, which attended Quaker meetings, listened to a lot of NPR.)

He was a weird, intense kid. He experienced something like ego death while snow-angeling in fresh Vermont powder when he was 12: “direct knowledge that I, that I, is all living things. That I am this whole planet of living things.” He recalled pestering his mothers’ friends “about how we’re going to save the world and you’re not doing it” when they came over. He never recovered from seeing Terminator 2: Judgment Day as a teenager.

I asked him whether some personal experience of trauma or hardship had made him so aware of the horrors of the world. Nope.

Forall attended Williams College for a year, studying economics. But, he told me, he was racked with questions no professor or textbook could provide the answer to. Is it true that we are just matter, just chemicals? Why is there so much suffering? To find the answer, at 18, he dropped out and moved to a 300-year-old Zen monastery in Japan.

Folks unfamiliar with different types of Buddhism might imagine Zen to be, well, zen. This would be a misapprehension. Zen practitioners are not unlike the Trappists: ascetic, intense, renunciatory. Forall spent years begging, self-purifying, and sitting in silence for months at a time. (One of the happiest moments of his life, he told me, was toward the end of a 100-day sit.) He studied other Buddhist traditions and eventually, he added, did go back and finish his economics degree at Williams, to the relief of his parents.

He got his answer: Craving is the root of all suffering. And he became ordained, giving up the name Teal Scott and becoming Soryu Forall: “Soryu” meaning something like “a growing spiritual practice” and “Forall” meaning, of course, “for all.”

Back in Vermont, Forall taught at monasteries and retreat centers, got kids to learn mindfulness through music and tennis, and co-founded a nonprofit that set up meditation programs in schools. In 2013, he opened MAPLE, a “modern” monastery addressing the plagues of environmental destruction, lethal weapons systems, and AI, offering co-working and online courses as well as traditional monastic training.

In the past few years, MAPLE has become something of the house monastery for people worried about AI and existential risk. This growing influence is manifest on its books. The nonprofit’s revenues have quadrupled, thanks in part to contributions from tech executives as well as organizations such as the Future of Life Institute, co-founded by Jaan Tallinn, a co-creator of Skype. The donations have helped MAPLE open offshoots—Oak in the Bay Area, Willow in Canada—and plan more. (The highest-paid person at MAPLE is the property manager, who earns roughly $40,000 a year.)

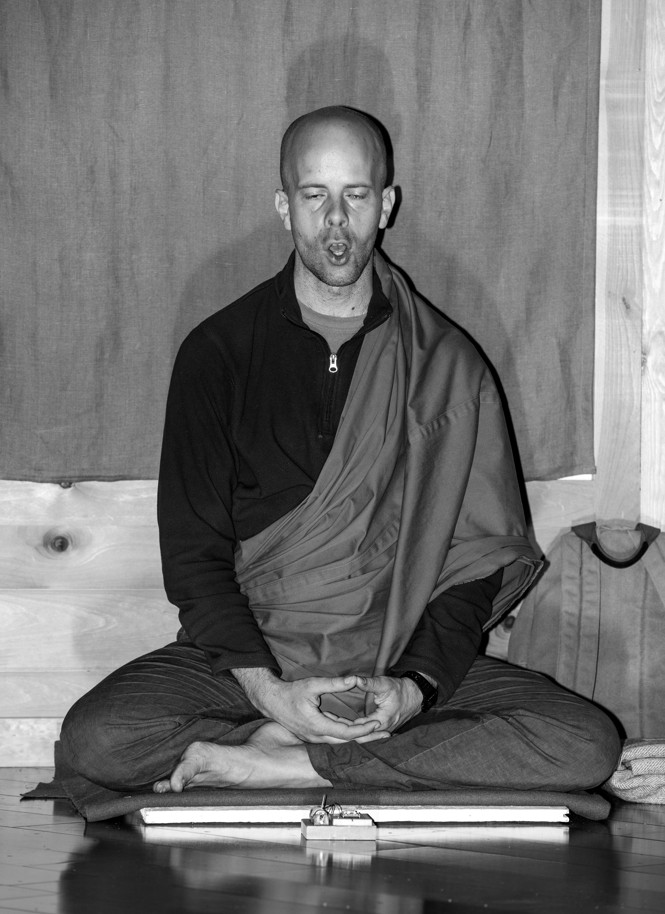

MAPLE is not technically a monastery, as it is not part of a specific Buddhist lineage. Still, it is a monastery. At 4:40 a.m., the Zendo is full. The monks and novices sit in silence below signs that read, among other things, abandon all hope, this place will not support you, and nothing you can think of will help you as you die. They sing in Pali, a liturgical language, regaling the freedom of enlightenment. They drone in English, talking of the Buddha. Then they chant part of the heart sutra to the beat of a drum, becoming ever louder and more ecstatic over the course of 30 minutes: “Gyate, gyate, hara-gyate, hara-sogyate, boji sowaka!” “Gone, gone, gone all the way over, everyone gone to the other shore. Enlightenment!”

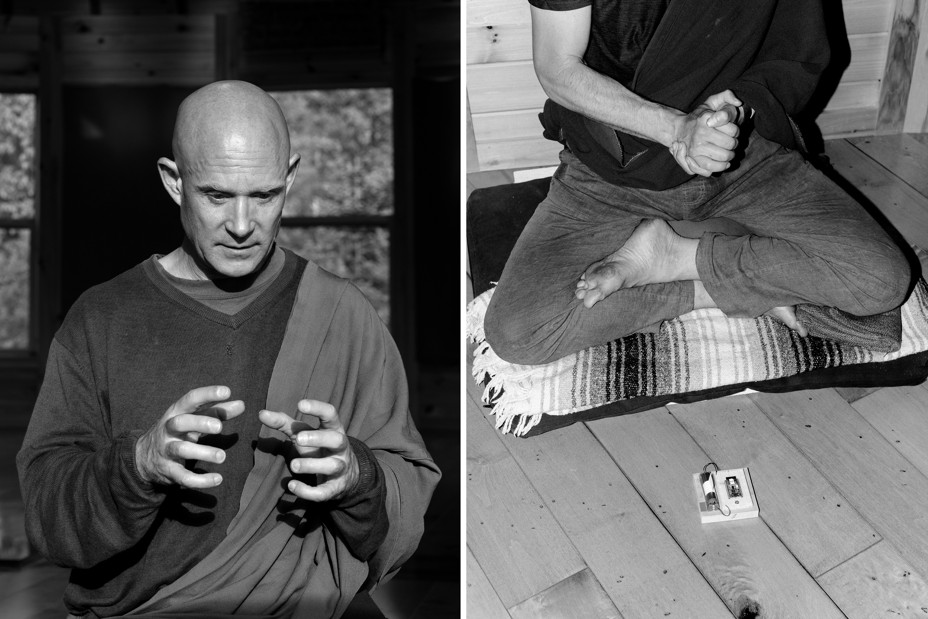

The residents maintain a strict schedule, much of it in silence. They chant, meditate, exercise, eat, work, eat, work, study, meditate, and chant. During my visit, the head monk asked someone to breathe more quietly during meditation. Over lunch, the congregants discussed how to remove ticks from your body without killing them (I do not think this is possible). Forall put in a request for everyone to “chant more beautifully.” I observed several monks pouring water in their bowl to drink up every last bit of food.

The strictness of the place helps them let go of ego and see the world more clearly, residents told me. “To preserve all life: You can’t do that until you come to love all life, and that has to be trained,” a 20-something named Bodhi Joe Pucci told me.

Many people find their time at MAPLE transformative. Others find it traumatic. I spoke with one woman who said she had experienced a sexual assault during her time at Oak in California. That was hard enough, she told me. But she felt more hurt by the way the institution responded after she reported it to Forall and later to the nonprofit’s board, she said: with a strange, stony silence. (Forall told me that he cared for this person, and that MAPLE had investigated the claims and didn’t find “evidence to support further action at this time.”) The message that MAPLE’s culture sends, the woman told me, is: “You should give everything—your entire being, everything you have—in service to this organization, because it’s the most important thing you could ever do.” That culture, she added, “disconnected people from reality.”

While the residents are chanting in the Zendo, I notice that two are seated in front of an electrical device, its tiny green and red lights flickering as they drone away. A few weeks earlier, several residents had constructed place-mat-size wooden boards with accelerometers in them. The monks would sit on them while the device measured how on the beat their chanting was: green light, good; red light, bad.

Chanting on the beat, Forall acknowledged, is not the same thing as cultivating universal empathy; it is not going to save the world. But, he told me, he wanted to use technology to improve the conscientiousness and clarity of MAPLE residents, and to use the conscientiousness and clarity of MAPLE residents to improve the technology all around us. He imagined changes to human “hardware” down the road—genetic engineering, brain-computer interfaces—and to AI systems. AI is “already both machine and living thing,” he told me, made from us, with our data and our labor, inhabiting the same world we do.

Does any of this make sense? I posed that question to an AI researcher named Sahil, who attended one of MAPLE’s retreats earlier this year. (He asked me to withhold his last name because he has close to zero public online presence, something I confirmed with a shocked, admiring Google search.)

He had gone into the retreat with a lot of skepticism, he told me: “It sounds ridiculous. It sounds wacky. Like, what is this ‘woo’ shit? What does it have to do with engineering?” But while there, he said, he experienced something spectacular. He was suffering from “debilitating” back pain. While meditating, he concentrated on emptying his mind and found his back pain becoming illusory, falling away. He felt “ecstasy.” He felt like an “ice-cream sandwich.” The retreat had helped him understand more clearly the nature of his own mind, and the need for better AI systems, he told me.

That said, he and some other technologists had reviewed one of Forall’s ideas for AI technology and “completely tore it apart.”

Does it make any sense for us to be worried about this at all? I asked myself that question as Forall and I sat on a covered porch, drinking tea and eating dates stuffed with almond butter that a resident of the monastery wordlessly dropped off for us. We were listening to birdsong, looking out on the Green Mountains rolling into Canada. Was the world really ending?

Forall was absolute: Nine countries are armed with nuclear weapons. Even if we stop the catastrophe of climate change, we will have done so too late for thousands of species and billions of beings. Our democracy is fraying. Our trust in one another is fraying. Many of the very people creating AI believe it could be an existential threat: One 2022 survey asked AI researchers to estimate the probability that AI would cause “severe disempowerment” or human extinction; the median response was 10 percent. The destruction, Forall said, is already here.

[Read: AI doomerism is a decoy]

But other experts see a different narrative. Jaron Lanier, one of the inventors of virtual reality, told me that “giving AI any kind of a status as a proper noun is not, strictly speaking, in some absolute sense, provably incorrect, but is pragmatically incorrect.” He continued: “If you think of it as a non-thing, just a collaboration of people, you gain a lot in terms of thoughts about how to make it better, or how to manage it, or how to deal with it. And I say that as somebody who’s very much in the center of the current activity.”

I asked Forall whether he felt there was a risk that he was too attached to his own story about AI. “It’s important to know that we don’t know what’s going to happen,” he told me. “It’s also important to look at the evidence.” He said it was clear we were on an “accelerating curve,” in terms of an explosion of intelligence and a cataclysm of death. “I don’t think that these systems will care too much about benefiting people. I just can’t see why they would, in the same way that we don’t care about benefiting most animals. While it is a story in the future, I feel like the burden of proof isn’t on me.”

That evening, I sat in the Zendo for an hour of silent meditation with the monks. A few times during my visit to MAPLE, a resident had told me that the greatest insight they achieved was during an “interview” with Forall: a private one-on-one instructional session, held during zazen. “You don’t experience it elsewhere in life,” one student of Forall’s told me. “For those seconds, those minutes that I’m in there, it is the only thing in the world.”

Toward the very end of the hour, the head monk called out my name, and I rushed up a rocky path to a smaller, softly lit Zendo, where Forall sat on a cushion. For 15 minutes, I asked questions and received answers from this unknowable, unusual brain—not about AI, but about life.

When I returned to the big Zendo, I was surprised to find all of the other monks still sitting there, waiting for me, meditating in the dark.